The name Socrates is synonymous with the foundations of Western philosophy, but few recognize his profound impact on the technological advancements we enjoy today. As the editors of DailyTechPosts, we're excited to dive into the life and legacy of this brilliant thinker, whose pioneering ideas continue to shape the modern world.

Born in Athens around 470 BC, Socrates didn't leave behind any writings of his own. Yet, his unparalleled contributions to logic, reason, and the pursuit of knowledge reverberate through the ages. Inspired by his mentor, Parmenides, Socrates developed a unique method of questioning that pushed his contemporaries to think deeply and challenge long-held assumptions. This "Socratic method" lies at the heart of how we approach problem-solving, scientific inquiry, and the advancement of knowledge today.

Socrates' critical questioning and tireless search for truth influenced not only his students, like the famous philosophers Plato and Xenophon, but also the very foundations of modern technology. His emphasis on empiricism, deductive reasoning, and the importance of understanding root causes foreshadowed the rise of the scientific method - the bedrock upon which all technological progress is built.

Just imagine how your favorite tech devices, from smartphones to self-driving cars, would not exist without the pioneering spirit of this ancient Greek thinker. Socrates' legacy lives on in the way we approach complex challenges, test hypotheses, and build innovative solutions to improve our world.

As you delve into the captivating biography that follows, prepare to be amazed by the life and times of this extraordinary individual. Socrates' timeless wisdom continues to inspire new generations of thinkers, inventors, and visionaries who are shaping the future of technology. Join us on this journey to uncover the Socratic roots of our modern, interconnected world.

Socrates, born in Athens around 470/469 BC, remains one of the most enigmatic figures in the annals of philosophy.

The son of Sophroniscus, a sculptor, and Phaenarete, a midwife, Socrates received the education typical of late 5th century Athenian youth. The most important influence on his intellectual development was his interaction with the Sophists who frequented Athens. Socrates took part in three military campaigns at Potidaea (432-429), Delium (424) and Amphipolis (422) and distinguished himself with his bravery, physical vigor and near Spartan indifference to the harshness of the elements. He was an good citizen but only served once on the Council of 500. He was aloof from politics because of his attention to philosophy, the "love of wisdom." The Oracle at Delphi announced him the wisest man in the world, but he wrote no books. His acquaintances were tied to him by bonds of friendship and admiration -- there was no formal bond of discipleship.

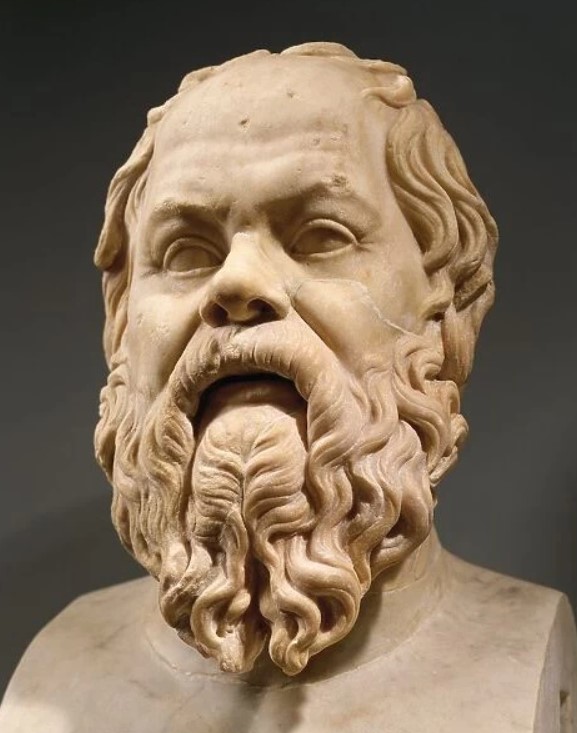

From two of his friends, Xenophon (c.435-354 B.C.) and Plato (c.430-c.354 B.C.), we can learn all we know with certainty about the personality of Socrates. Plato often makes Socrates the mouthpiece of ideas that in all probability were not necessarily held by Socrates. Trained as a soldier and not a philosopher, Xenophon makes Socrates a more commonplace person that he probably was. Given the above, we can be assured that Socrates was a bit on the ugly side and overweight. His wife, Xanthippe, was supposed to have been something of a shrew.

Socrates spoke of the "divine sign," a supernatural voice that always prevented him from doing wrong. He was charged in 399 B.C. as "an evil doer and a curious person, searching into things under the earth and above the heaven; and making the worse appear the better cause, and teaching all this to others." The substance of Socrates defense appears in Plato's Apology.

Socrates was condemned by a majority of six votes in a jury numbering 500. He refused to contemplate the alternative to death. Thirty days elapsed because of a sacred mission to Delos. Socrates' friends planned his escape but he refused their offer. Having spent his last days conversing with his friends, as Plato relates in his Phaedo, Socrates drank the fatal dose of hemlock and died.

For Socrates, virtue was knowledge and knowledge was to be obtained by the dialectical technique he borrowed from Zeno. With irony, Socrates would pose the question "what is courage?" He claimed he did not know the answer. But by the skilled use of questions and answers, Socrates would "lead" the student to knowledge. His aim was to act as a midwife to those in labor for knowledge. Such is the Socratic style.