At dailytechposts.com, we're always on the lookout for unconventional influences in the tech world. Today, we're diving into the surprising impact of Niccolò Machiavelli on modern technology and engineering.

You might raise an eyebrow at the mention of a 16th-century Italian diplomat in a tech context, but hear us out. Machiavelli's strategic thinking has quietly revolutionized how we approach technological challenges:

- Cybersecurity: His concepts of power and defense inform modern network protection strategies.

- AI Ethics: Machiavellian ideas spark debates on the moral implications of artificial intelligence.

- Project Management: "The Prince" offers insights that shape agile methodologies in software development.

- Corporate Strategy: Tech giants apply Machiavellian principles in competitive market tactics.

- User Experience: His understanding of human nature influences design psychology.

Intrigued? Join us as we explore how this Renaissance thinker nfluenced the formation of modern technical strategy.

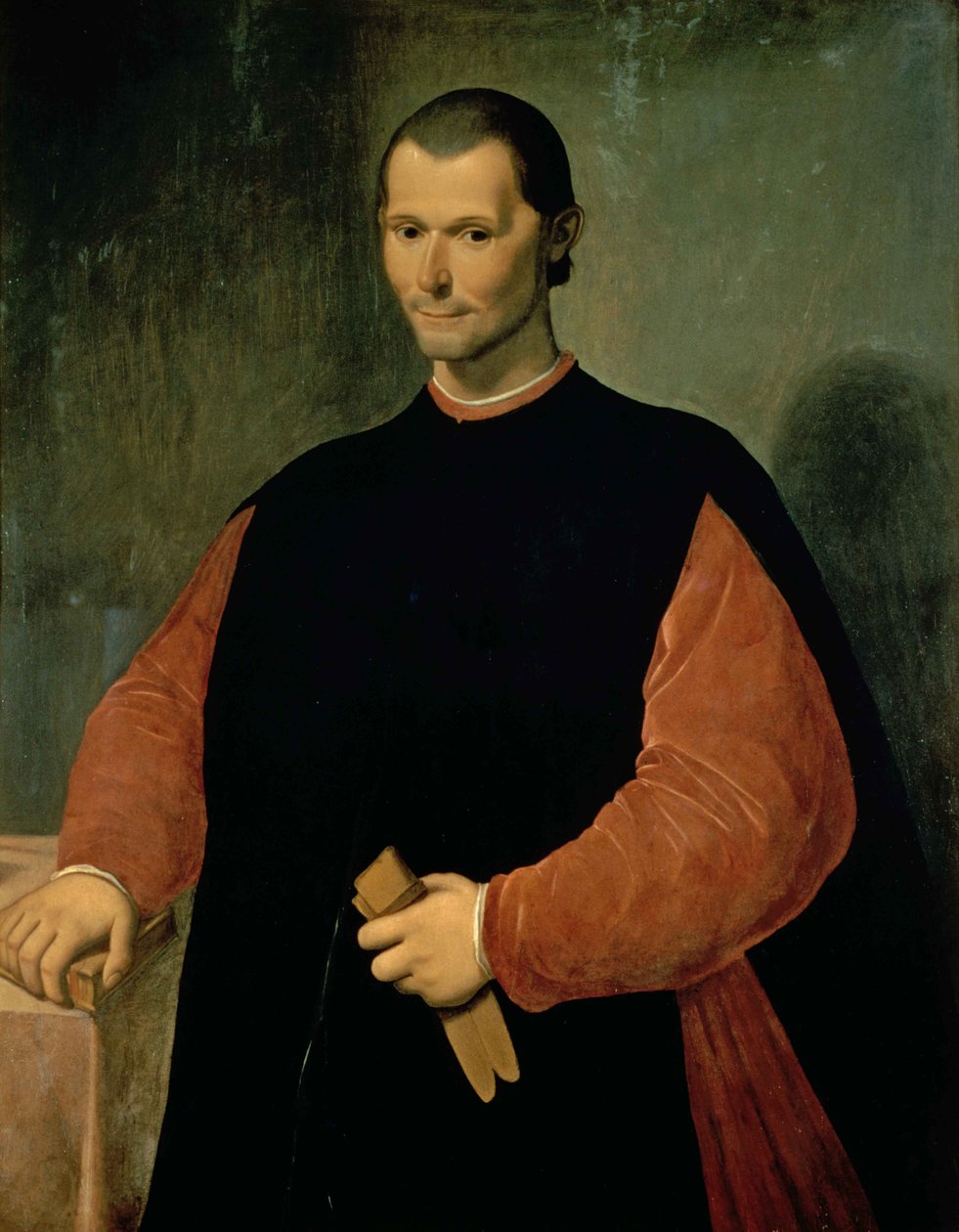

The father of modern political theory, Niccolo Machiavelli, was born at Florence in 1469, saw the troubles of the French invasion (1493), when the Medici fled, and in 1498 became secretary of the Ten, until the fall of the republic in 1512.

He was employed in a great variety of missions, including one to the Emperor Maximilian, and four to France. His dispatches during these journeys, and his treatises on the Affairs of France and Germany, are full of far-reaching insight. On the restoration of the Medici, Machiavelli was involved in the downfall of his patron, Gonfaloniere Soderini. Arrested on a charge of conspiracy in 1513, and put to the torture, he disclaimed all knowledge of the alleged conspiracy. Although pardoned, he was obliged to retire from public life and devoted himself to literature.

It was not until 1519 that he was commissioned by Leo X to draw up his report on a reform of the state of Florence. In 1521-25 he was employed in diplomatic services and as historiographer. After the defeat of the French at Pavia (1525), Italy was helpless before the advancing forces of the Emperor Charles V and Machiavelli strove to avert from Florence the invading army on its way to Rome. In May 1527 the Florentines again drove out the Medici and proclaimed the republic - but Machiavelli, bitterly disappointed that he was to be allowed no part in the movement for liberty, and already in declining health, died on June 22.

Through misrepresentation and misunderstanding his writings were spoken of as almost diabolical, his most violent assailants being the clergy. The first great edition of his works was not issued until 1782. From that period his fame as the founder of political science has steadily increased.

Besides his letters and state papers, Machiavelli's historical writings comprise Florentine Histories, Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livius (commonly known as The Discourses), a Life of Castruccio Castrancani (unfinished) and History of the Affairs of Lucca. His literary works comprise an imitation of the Golden Ass of Apuleius, an essay on the Italian language, the play Mandragola, and several minor compositions. He also wrote Seven Books on the Art of War.

The greatest source of Machiavelli's reputation is, of course, The Prince (1532). The main theme of this short book is that all means may be resorted to for the establishment and preservation of authority -- the end justifies the means -- and that the worst and most treacherous acts of the ruler are justified by the wickedness and treachery of the governed. The Prince was condemned by Pope Clement VIII. See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for a sound biography of Machiavelli.

* * *

Introduction to Book One of Machiavelli's Discourses on Titus Livius.

Although the envious nature of men, so prompt to blame and so slow to praise, makes the discovery and introduction of any new principles and systems as dangerous almost as the exploration of unknown seas and continents, yet, animated by that desire which impels me to do what may prove for the common benefit of all, I have resolved to open a new route, which is not yet been followed by any one, and may prove difficult and troublesome, but may also bring me some reward in the approbation of those who will kindly appreciate my efforts.

And if my poor talents, my little experience of the present and insufficient study of the past, should make the result of my labors defective and of little utility, I shall at least have shown the way to others, who will carry out my views with greater ability, eloquence, and judgment, so that if I do not merit praise, I ought at least not to incur censure.

When we consider the general respect for antiquity, and how often -- to say nothing of other examples -- a great price is paid for some fragments of an antique statue, which we are anxious to possess to ornament our houses with, or to give to artists who strive to imitate them in their own works; and when we see, on the other hand, the wonderful examples which the history of ancient kingdoms and republics present to us, the prodigies of virtue and of wisdom displayed by the kings, captains, citizens, and legislators who have sacrificed themselves for their country, -- when we see these, I say, more admired than imitated, or so much neglected that not the least trace of this ancient virtue remains, we cannot but be at the same time as much surprised as afflicted.

Though more so as in the differences which arise between citizens, or in the maladies to which they are subjected, we see the same people have recourse to the judgments and remedies prescribed by the ancients. The civil laws are in fact nothing but decisions given by their jurisconsults, and which, reduced to a system, direct our modern jurists in their decisions.

And what is the science of medicine, but the experience of ancient physicians, which their successors have taken for their guide? And yet to found a republic, maintain states, to govern a kingdom, organize an army, conduct a war, dispense justice, and extend empires, you'll find neither prince, nor republic, nor captain, nor citizen, who has recourse to the examples of antiquity! This neglect, I am persuaded, is due less to the weakness to which the vices of our education have reduced the world, than to the evils caused by the proud indolence which prevails in most of the Christian states, and to the lack of real knowledge of history, the true sense of which is not known, or the spirit of which they do not comprehend. Thus the majority of those who read it take pleasure only in a variety of the events which history relates, without ever thinking of imitating the noble actions, deeming that not only difficult, but impossible; as though heaven, the sun, the elements, and then had changed the order of emotions and power, and were different from what they were in ancient times.

Wishing, therefore, so far as in me lies, to draw mankind from this error, I have thought it proper to write upon those books of Titus Livius that have come to us entire despite the malice of time; touching upon all those matters which, after a comparison between the ancient and modern events, may seem to me necessary to facilitate their proper understanding. In this way those who read my remarks may derive those advantages which should be the name of all study of history; and although the undertaking is difficult, yet, aided by those who have encouraged me in this attempt, I hope to carry it sufficiently far, so that but little may remain for others to carry it to its destined end.

[Source: Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince and The Discourses, Introduction by Max Lerner (New York: Modern Library,1950), pp. 103-105.]

More information about Niccolo Machiavelli you can see here: