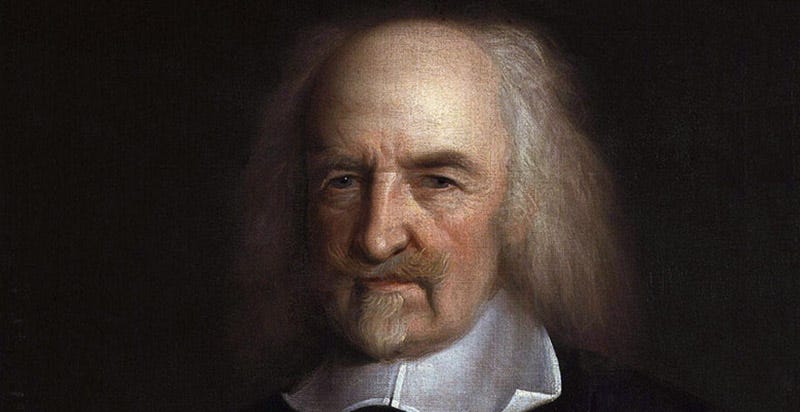

The year is 1588. As the Spanish Armada looms on the horizon, a young Thomas Hobbes enters the world - destined to become one of the most influential philosophers and thinkers of his time. Little did he know that his brilliant, analytical mind would go on to revolutionize our understanding of government, human nature, and the very fabric of society.

Born during a period of immense political turmoil, Hobbes would go on to witness first-hand the upheaval of the English Civil War. This turbulent backdrop fueled his landmark work, Leviathan, which presented a revolutionary new social contract theory that sought to establish a stable, sovereign authority to prevent the chaos of a "state of nature." This groundbreaking text, which you'll discover in more detail below, would cement Hobbes' reputation as a visionary thinker whose ideas continue to shape our world today.

But Hobbes' contributions extend far beyond political philosophy. The man was a true polymath, dabbling in mathematics, physics, and even early theories of computing. In fact, his concepts of automated reasoning and the mechanization of the mind predate modern computer science by centuries. Hobbes envisioned a world where machines could one day imitate human cognition - a vision that has guided the development of artificial intelligence to this very day.

So join us as we dive into the extraordinary life and legacy of Thomas Hobbes - a man whose penetrating intellect and insatiable curiosity pushed the boundaries of human knowledge and left an indelible mark on the technological landscape. From the origins of modern political thought to the dawn of the digital age, Hobbes' impact is undeniable. Prepare to be inspired by the remarkable story of this true Renaissance man.

The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) is best known for his political thought, and deservedly so. His vision of the world is strikingly original and still relevant to contemporary politics.

His main concern is the problem of social and political order: how human beings can live together in peace and avoid the danger and fear of civil conflict. He poses stark alternatives: we should give our obedience to an unaccountable sovereign (a person or group empowered to decide every social and political issue). Otherwise what awaits us is a state of nature that closely resembles civil war – a situation of universal insecurity, where all have reason to fear violent death and where rewarding human cooperation is all but impossible.

One controversy has dominated interpretations of Hobbes. Does he see human beings as purely self-interested or egoistic? Several passages support such a reading, leading some to think that his political conclusions can be avoided if we adopt a more realistic picture of human nature. However, most scholars now accept that Hobbes himself had a much more complex view of human motivation. A major theme below will be why the problems he poses cannot be avoided simply by taking a less selfish view of human nature.

Life and Times

Hobbes’s biography is dominated by the political events in England and Scotland during his long life. Born in 1588, the year the Spanish Armada made its ill-fated attempt to invade England, he lived to the exceptional age of 91, dying in 1679. He was not born to power or wealth or influence: the son of a disgraced village vicar, he was lucky that his uncle was wealthy enough to provide for his education and that his intellectual talents were soon recognized and developed (through thorough training in the classics of Latin and Greek). Those intellectual abilities, and his uncle’s support, brought him to university at Oxford.

And these in turn—together with a good deal of common sense and personal maturity—won him a place tutoring the son of an important noble family, the Cavendishes. This meant that Hobbes entered circles where the activities of the King, of Members of Parliament, and of other wealthy landowners were known and discussed, and indeed influenced. Thus intellectual and practical ability brought Hobbes to a place close to power—later he would even be math tutor to the future King Charles II. Although this never made Hobbes powerful, it meant he was acquainted with and indeed vulnerable to those who were.

Two Intellectual Influences

As well as the political background just stressed, two influences are extremely marked in Hobbes’s work. The first is a reaction against religious authority as it had been known, and especially against the scholastic philosophy that accepted and defended such authority. The second is a deep admiration for (and involvement in) the emerging scientific method, alongside an admiration for a much older discipline, geometry. Both influences affected how Hobbes expressed his moral and political ideas. In some areas it is also clear that they significantly affected the ideas themselves.

Ethics and Human Nature

Hobbes’s moral thought is difficult to disentangle from his politics. On his view, what we ought to do depends greatly on the situation in which we find ourselves. Where political authority is lacking (as in his famous natural condition of mankind), our fundamental right seems to be to save our skins, by whatever means we think fit. Where political authority exists, our duty seems to be quite straightforward: to obey those in power.

The Natural Condition of Mankind

The state of nature is “natural” in one specific sense only. For Hobbes political authority is artificial: in the “natural” condition human beings lack government, which is an authority created by men. What is Hobbes’s reasoning here? He claims that the only authority that naturally exists among human beings is that of a mother over her child, because the child is so very much weaker than the mother (and indebted to her for its survival). Among adult human beings this is invariably not the case. Hobbes concedes an obvious objection, admitting that some of us are much stronger than others.

And although he is very sarcastic about the idea that some are wiser than others, he does not have much difficulty with the idea that some are fools and others are dangerously cunning. Nonetheless, it is almost invariably true that every human being is capable of killing any other. “Even the strongest must sleep; even the weakest might persuade others to help him kill another”. (Leviathan, xiii.1-2) Because adults are equal in this capacity to threaten one another’s lives, Hobbes claims there is no natural source of authority to order their lives together. (He is strongly opposing arguments that established monarchs have a natural or God-given right to rule over us.)

Conclusion

What happens, then, if we do not follow Hobbes in his arguments that judgment must, by necessity or by social contract or both, be the sole province of the sovereign? If we are optimists about the power of human judgment, and about the extent of moral consensus among human beings, we have a straightforward route to the concerns of modern liberalism. Our attention will not be on the question of social and political order, rather on how to maximize liberty, how to define social justice, how to draw the limits of government power, and how to realize democratic ideals. We will probably interpret Hobbes as a psychological egoist, and think that the problems of political order that obsessed him were the product of an unrealistic view of human nature, or unfortunate historical circumstances, or both. In this case, I suggest, we might as well not have read Hobbes at all.

More Information On Hobbes' life see the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the MacTutor.

CHAPTER XIII: Of the NATURAL CONDITION of mankind, as concerning their Felicity, and Misery

NATURE hath made men so equal in the faculties of body and mind as that, though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body or of quicker mind than another, yet when all is reckoned together the difference between man and man is not so considerable as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit to which another may not pretend as well as he. For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination or by confederacy with others that are in the same danger with himself.

And as to the faculties of the mind, setting aside the arts grounded upon words, and especially that skill of proceeding upon general and infallible rules, called science, which very few have and but in few things, as being not a native faculty born with us, nor attained, as prudence, while we look after some what else, I find yet a greater equality amongst men than that of strength. For prudence is but experience, which equal time equally bestows on all men in those things they equally apply themselves unto.

That which may perhaps make such equality incredible is but a vain conceit of one's own wisdom, which almost all men think they have in a greater degree than the vulgar; that is, than all men but themselves, and a few others, whom by fame, or for concurring with themselves, they approve. For such is the nature of men that how so ever they may acknowledge many others to be more witty, or more eloquent or more learned, yet they will hardly believe there be many so wise as themselves; for they see their own wit at hand, and other men's at a distance. But this proveth rather that men are in that point equal, than unequal. For there is not ordinarily a greater sign of the equal distribution of any thing than that every man is contented with his share.

From this equality of ability arise the quality of hope in the attaining of our ends. And therefore if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their end (which is principally their own conservation, and sometimes their delectation only) endeavour to destroy or subdue one another. And from hence it comes to pass that where an invader hath no more to fear than another man's single power, if one plant, sow, build, or possess a convenient seat, others may probably be expected to come prepared with forces united to dispossess and deprive him, not only of the fruit of his labour, but also of his life or liberty. And the invader again is in the like danger of another.

CHAPTER XIV Of the first and second NATURAL LAWS, and of CONTRACTS

THE right of nature, which writers commonly call jus naturale, is the liberty each man hath to use his own power as he will himself or the preservation of his own nature; that is to say, of his own life; and consequently, of doing anything which, in his own judgement and reason, he shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto.

By liberty is understood, according to the proper signification of the word, the absence of external impediments; which impediments may oft take away part of a man's power to do what he would, but cannot hinder him from using the power left him according as his judgement and reason shall dictate to him.

A law of nature

Is a precept, or general rule, found out by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do that which is destructive of his life, or taketh away the means of preserving the same, and to omit that by which he thinketh it may be best preserved. For though they that speak of this subject use to confound jus and lex, right and law, yet they ought to be distinguished, because right consisteth in liberty to do, or to forbear; whereas law determineth and bindeth to one of them: so that law and right differ as much as obligation and liberty, which in one and the same matter are inconsistent.

More information about Thomas Hobbes | State of Nature and Social Contract Theory in video